Mushrooms are one of the most intriguing organisms on Earth, contributing to both ecological systems and human well-being in numerous ways. From their role as decomposers to their importance in cuisine and medicine, mushrooms are far more than just culinary delicacies. They are a critical component of ecosystems, recycling nutrients and forming symbiotic relationships with plants and other organisms.

Mushrooms are the fruiting bodies of fungi, specifically belonging to the kingdom Fungi, which is distinct from plants and animals. Unlike plants, mushrooms do not perform photosynthesis. Instead, they obtain nutrients through absorption, breaking down organic material in their environment. Fungi play vital roles as decomposers, symbionts, and sometimes even parasites.

Fungi encompass a vast diversity of species, with estimates suggesting there are millions of fungal species, of which around 14,000 produce mushrooms that we recognize. These mushrooms are part of a larger organism hidden from view—an underground network of thread-like structures called mycelium.

The Importance of Mushrooms in Ecosystems

Mushrooms are crucial in many ecosystems because they help recycle nutrients by breaking down dead organic matter. They decompose leaves, wood, and other organic materials, converting them into simpler compounds that plants can use for growth. This process makes mushrooms key players in nutrient cycling and forest health.

Additionally, mushrooms form mycorrhizal relationships with plants, helping them absorb water and nutrients, particularly phosphorus. In return, the plant provides the fungus with sugars produced via photosynthesis.

The Life Cycle of Mushrooms

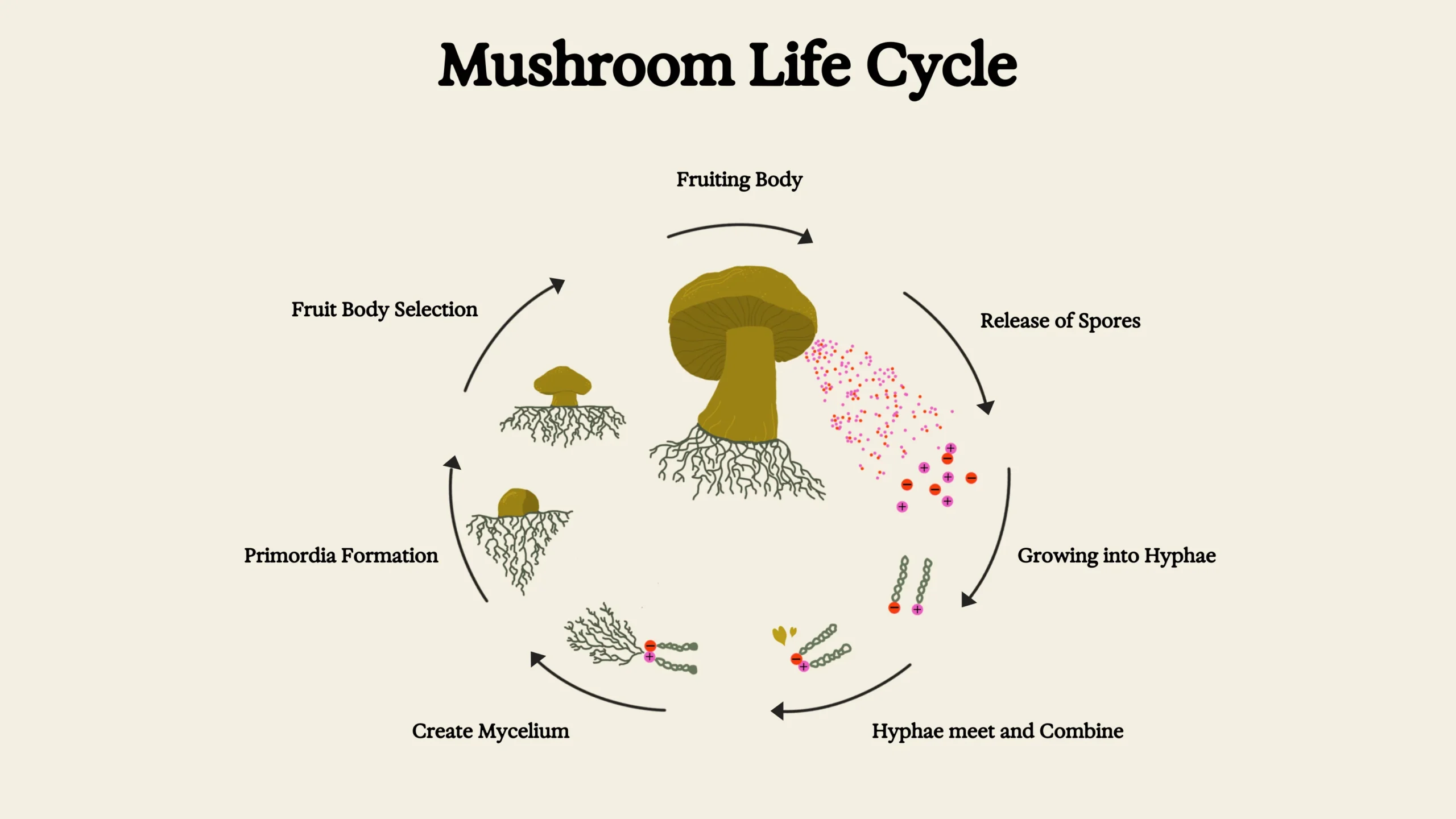

The life cycle of a mushroom is a fascinating process that involves several stages. Each stage is influenced by environmental conditions such as temperature, humidity, and substrate availability. Understanding this cycle is essential for those involved in mushroom cultivation and conservation.

Stage 1: Spore Formation

The mushroom life cycle begins with spores, microscopic cells that function similarly to seeds in plants. However, spores are much smaller and more lightweight, allowing them to disperse easily in the wind. Each mature mushroom can release billions of spores from structures like gills, pores, or teeth located beneath the cap. The process of spore formation occurs through meiosis, leading to genetically diverse spores capable of surviving in diverse environments.

Spores can remain dormant for extended periods, awaiting the right conditions to germinate. They are hardy and can survive in harsh environments until they find a suitable habitat with the necessary moisture, temperature, and nutrients.

Stage 2: Germination and Mycelium Growth

Once a spore lands in an ideal environment—typically moist soil, wood, or decaying organic material—it germinates. During germination, the spore begins to grow into a network of hyphae, the filamentous cells that make up the vegetative structure of the fungus. This network of hyphae, collectively called mycelium, spreads out in search of food sources.

At this stage, individual hyphae from different spores may come into contact with each other. If compatible, they can fuse, leading to the formation of a more complex mycelium capable of sexual reproduction. The fusion of hyphae allows for the sharing of genetic material, increasing the chances of producing genetically diverse fruiting bodies.

Stage 3: Mycelium Maturation and Colonization

As the mycelium network matures, it continues to spread and colonize its substrate, breaking down organic material to absorb nutrients. This process is crucial for the fungus, as it stores energy and builds the necessary components for fruiting body formation.

The mycelium can live for years, expanding underground or within a decaying log. During this phase, the mycelium may enter symbiotic relationships with plants (in the case of mycorrhizal fungi) or act as decomposers, consuming dead organic matter.

Mycelial growth is highly sensitive to environmental conditions. The substrate’s nutrient availability, moisture content, and temperature all play a role in determining how quickly and efficiently the mycelium can colonize.

Stage 4: Primordia Formation

Once the mycelium has thoroughly colonized its environment and environmental conditions are favorable (often in response to changes in temperature or moisture), it initiates the process of forming fruiting bodies. The first visible sign of this is the formation of primordia, small, knot-like structures that emerge from the mycelium.

Primordia are the early developmental stage of mushrooms. These small bumps eventually grow into fully formed mushrooms. At this point, environmental factors such as light and oxygen become crucial for the development of the fruiting bodies.

Stage 5: Fruiting Body Development

The primordia grow rapidly, forming the mature fruiting body, commonly known as the mushroom. The mushroom is the reproductive structure of the fungus, designed to produce and release spores.

The fruiting body consists of several parts:

- Cap (Pileus): The top portion, often umbrella-shaped, where spore-producing structures are located.

- Gills (Lamellae): Thin, blade-like structures under the cap, where spores are produced and released. Some mushrooms may have pores or teeth instead of gills.

- Stem (Stipe): Supports the cap and helps elevate the mushroom, aiding in spore dispersal.

- Veil: A membrane that covers the gills in some mushrooms during early development. It may leave remnants as the mushroom matures, such as a ring on the stem.

Once the fruiting body is fully developed, it begins releasing spores, starting the cycle anew.

Stage 6: Spore Dispersal

The primary function of the mature mushroom is spore dispersal. Depending on the species, spores can be dispersed through various methods. For most mushrooms, wind is the primary dispersal agent. Spores are released into the air from the gills, pores, or teeth, carried by air currents to new locations.

Some mushrooms, such as puffballs, use mechanical force to release their spores, while others rely on animals or water for spore dispersal. Once the spores find a suitable substrate, they can germinate and begin the life cycle again.

Environmental Conditions Influencing the Life Cycle

The life cycle of mushrooms is closely tied to the environment. Specific conditions must be met for each stage, from spore germination to fruiting body formation.

The Role of Temperature and Humidity

Mushrooms are highly sensitive to temperature and moisture. Most species require a cool, moist environment to thrive, although some varieties, like desert fungi, are adapted to drier conditions. High humidity is essential for spore germination and the growth of mycelium, while temperature changes often trigger the formation of fruiting bodies.

For example, many species of mushrooms fruit in the fall when temperatures drop and moisture levels increase due to rainfall. This seasonal cycle ensures that the developing mushrooms have access to the necessary environmental resources.

Light and Dark Cycles

While mushrooms do not require sunlight for photosynthesis like plants, light can play a role in triggering the fruiting process. Some species need specific light conditions to begin developing fruiting bodies, though excessive light exposure can sometimes inhibit growth.

In general, mushrooms thrive in dark or low-light environments, making them well-suited for growth in forests, caves, and other shaded areas.

Nutrient Availability

The substrate on which a mushroom grows provides the nutrients it needs for mycelial growth and fruiting body development. Different species of fungi have varying nutritional requirements. Saprotrophic mushrooms, for example, break down dead organic material, while mycorrhizal mushrooms depend on symbiotic relationships with plants for their nutritional needs.

If the substrate lacks sufficient nutrients or becomes depleted, the mycelium may not be able to produce fruiting bodies, and the life cycle will pause until conditions improve.

Types of Mushrooms and Their Life Cycles

Different types of mushrooms have distinct life cycles depending on their ecological roles and relationships with other organisms. Broadly, mushrooms can be categorized as saprotrophic, mycorrhizal, parasitic, or endophytic.

Saprotrophic Mushrooms

Saprotrophic mushrooms, such as the common white button mushroom (Agaricus bisporus) and oyster mushrooms (Pleurotus ostreatus), are decomposers. They break down dead organic material, recycling nutrients into the ecosystem. Their life cycle relies on the availability of decaying matter like wood, leaves, or animal remains.

These mushrooms play an essential role in ecosystems, accelerating the decomposition process and ensuring that nutrients return to the soil.

Mycorrhizal Mushrooms

Mycorrhizal fungi form mutually beneficial relationships with plant roots. Notable examples include species of the genus Amanita and Boletus. In this symbiotic relationship, the fungus provides the plant with nutrients like phosphorus, while the plant supplies the fungus with sugars.

These fungi are crucial to forest health, as they enhance plant growth and survival. The life cycle of mycorrhizal mushrooms is closely linked to the plants they associate with, and they cannot complete their life cycle without this symbiotic relationship.

Parasitic Mushrooms

Parasitic mushrooms, such as the honey fungus (Armillaria), attack living plants, extracting nutrients from their hosts. These fungi can cause significant damage to forests and crops, as they weaken or kill their host plants.

Parasitic mushrooms typically have a life cycle that includes both saprotrophic and parasitic phases, often continuing to grow on the dead remains of their host after it has died.

Endophytic Mushrooms

Endophytic fungi live inside plants without causing harm, often providing benefits such as enhanced resistance to disease and environmental stress. Though not as well-studied as other fungal types, endophytic mushrooms are believed to play an essential role in plant health and ecosystem functioning.

5. The Role of Mushrooms in Human Life

Mushrooms have played significant roles in human cultures for millennia. They are valued for their culinary uses, medicinal properties, and spiritual significance.

Edible Mushrooms and Culinary Uses

Mushrooms are a rich source of nutrients, including protein, vitamins, and minerals. Edible species like shiitake, chanterelles, and portobellos are prized in cuisine worldwide. Their umami flavor makes them popular in various dishes, from soups and sauces to stir-fries and salads.

Medicinal Mushrooms

Medicinal mushrooms, such as Ganoderma lucidum (reishi) and Lentinula edodes (shiitake), have been used for centuries in traditional medicine. These fungi are believed to possess immune-boosting, anti-inflammatory, and antioxidant properties. Modern research is increasingly supporting their use in treating conditions ranging from infections to cancer.

Fungi in Traditional Cultures

Mushrooms also hold a place in traditional rituals and spiritual practices. Psychedelic mushrooms, such as those containing psilocybin, have been used for centuries in indigenous ceremonies to induce altered states of consciousness and facilitate spiritual experiences.

The Importance of Understanding Mushroom Life Cycles

The life cycle of mushrooms is a complex and fascinating process that reflects their critical role in ecosystems and human life. Understanding this life cycle not only benefits mushroom cultivation but also enhances our appreciation for these incredible organisms and their ecological significance.